by Jake Newby, MIBLUE DAILY, March 2025

The need for more diversity across the health care profession affects all areas of care and extends to the doula workforce. This disparity is one of many that the Grand Rapids African American Health Institute (GRAAHI) works to eradicate.

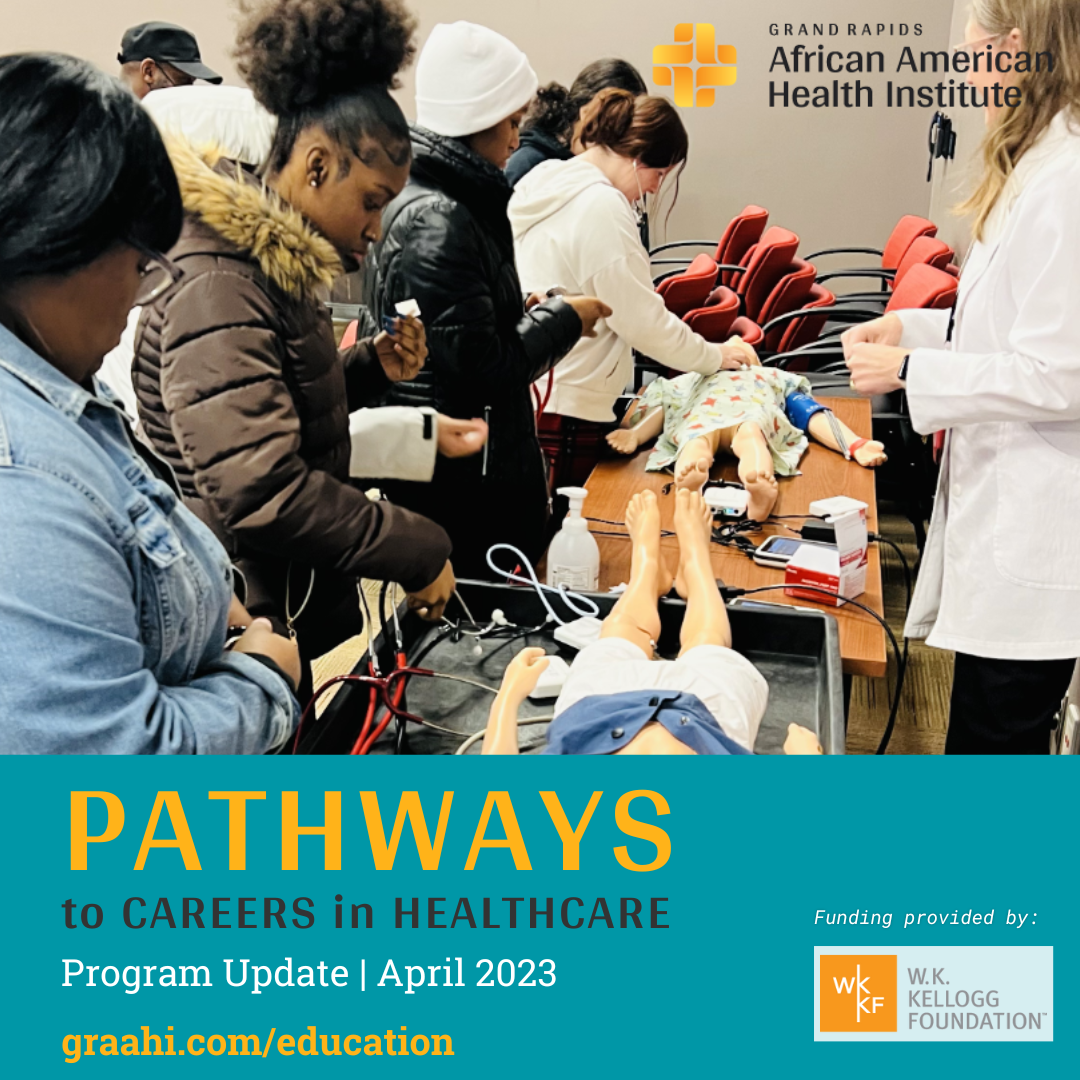

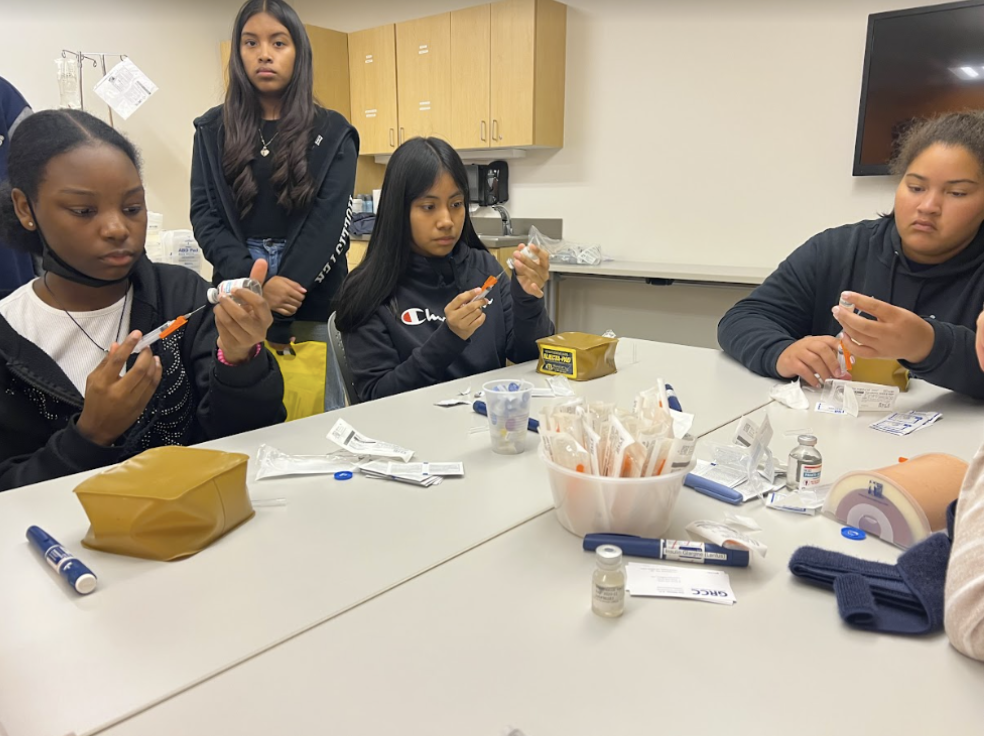

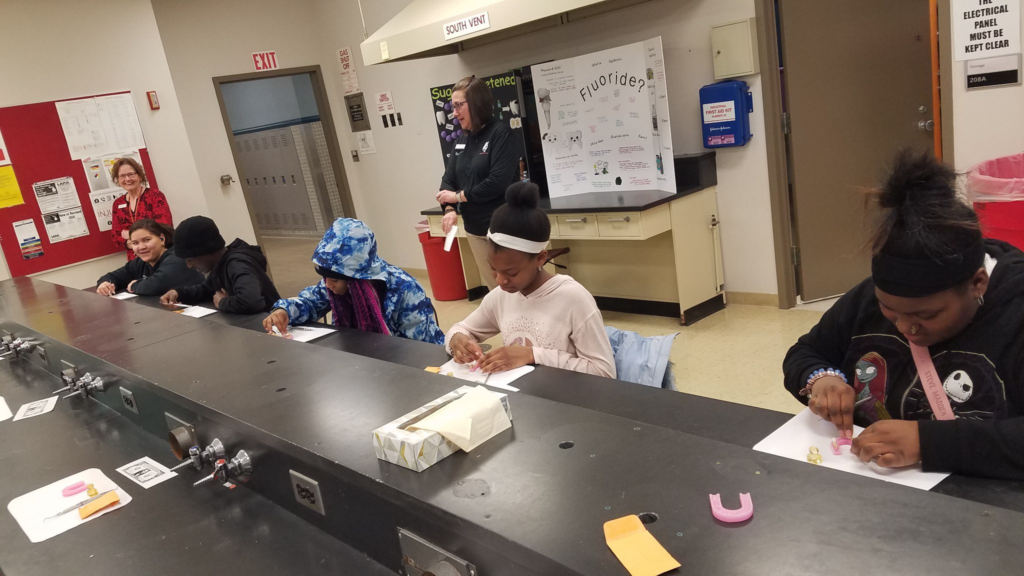

Through its multi-year MY PACE Program, the Black Womb Workers Doula Initiative supports adult learners interested in health care careers. GRAAHI’s Pathways to Health Care Careers Department aims to train 15 new doulas in Kent County in the first half of 2025. This program could prove to be a mutually beneficial victory for health equity in Kent County, Michigan by diversifying the area’s health care workforce and simultaneously improving maternal health outcomes for mothers who partner with doulas.

“Our program takes a comprehensive approach to prepare doulas as life-saving agents for Black moms and Black babies,” explained Vanessa Greene, CEO of GRAAHI “Black maternal health disparities are a crisis, and our doulas are trained to address systemic inequities head-on. They learn how to navigate healthcare systems, advocate for their clients, and provide holistic, non-medical support that extends far beyond the delivery room.

“Our goal is not only to reduce maternal and infant mortality rates but also to build a community of support that uplifts Black families,” Greene went on. “We want our doulas to be pillars of strength, knowledge, and compassion—offering the kind of care that saves lives and creates lasting, positive change in our communities.”

“We are focused on the certification piece by supporting workforce development,” said Dr. Te’Asia Jordan, GRAAHI’s director of education and access to health care careers. “Right now, that workforce is not reflective of the community. So, that means African Americans and Hispanics are underrepresented in the health care workforce. Our specific commitment is to empower individuals by providing the training and that certification the need to bring lifesaving information back to their communities.”

A 13-year study that observed nearly 1,900 mothers under the care of 574 doulas determined that support from a doula during labor and childbirth was associated with reduced cesarean section (C-section) frequency, low birth weight and premature labor. Doula care patients in the study were 89% more likely to start breastfeeding by six weeks when compared to standard care patients.

“A lot of people don’t even know what a doula is, and that includes adults who are not expecting,” said GRAAHI Post-Secondary Engagement Specialist Ashley Starr. “By offering education and creating opportunities, we aim to bring hope to the community. It’s a tragedy that the Black maternal mortality rate among Black women is so high. We believe that providing more knowledge and education can make a meaningful difference and inspire greater hope.”

Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation teams with GRAAHI to certify potentially dozens of new doulas from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds

In 2024, GRAAHI received a grant through the Advancing Maternal Health Equity program through a partnership of BCBSM Social Mission and the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation for $45,000, which the organization has dedicated to the Black Womb Workers program’s latest cohort of doula training and certification.

By reducing preventable complications and chronic conditions – such as C-sections and epidurals – and increasing breastfeeding, doulas offer an affordable solution for mothers who take advantage of their assistance, as they can reduce spending on these long-term adverse effects and sequelae. By providing funding, BCBSM helps contribute to mitigating these adverse outcomes.

“This funding will allow us to train and certify doulas across a wide age range, from 17-year-olds to retirees or those seeking a new career path,” Jordan explained. “It will cover the certification process and provide essential tools, such as a birthing ball and a yoga mat, to support the birthing individuals they assist. Additionally, it will help prepare them to be fully equipped, functional doulas serving families here in Kent County.”

Doula intervention is statistically proven to positively impact birthing outcomes, but doulas are rarely a part of the average mother’s birth care team. Factors like cost, lack of insurance and lack of awareness restrict doula access for many moms in the United States, particularly those living in low-income areas like Kent County. Many moms-to-be aren’t aware of what doulas are or the support they provide.

Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s “Healthy Moms, Healthy Babies” initiative expanded to include doula services for Medicaid recipients in 2023. In response, GRAAHI launched training programs to equip and deploy as many doulas as possible into Kent County.

Doulas do a lot to assist new moms, including the execution of a birth plan, which is a written outline of a mother’s preferences during labor and delivery.

“You don’t know what you don’t know, right?” Jordan said. “I’ve noticed that many expectant parents may have a general birth plan and focus primarily on their baby’s health during OBGYN visits, thinking that’s all there is to prepare. But there’s so much more to consider. A doula can provide personalized, non-medical support that a doctor might not have the capacity to offer—like grabbing you a sandwich, ensuring no one touches your feet if that’s your preference, or asking if you’d like the lights on or off. Doulas are there to support the entire birthing experience in ways that make you feel more comfortable and cared for.”

In 2025, Jordan would like to see GRAAHI train two new cohorts of doulas in Kent County. In addition to the cohort supported by BCBSM funding, she hopes a total of 30 new doulas are certified following a planned third cohort in the second half of 2025.

“I’d love to see all those doulas be partnered with at least one family,” Jordan said.

“We know that Black women in our country are more likely to die from pregnancy related causes than white women and non-white women. Doulas play an important in mitigating those disparities,” said Audrey Harvey, Executive Director and CEO of the BCBSM Foundation. “At the same time, we know representation matters and diversifying our health care professionals is hugely important to our future. GRAAHI works to deliver health equity in both areas, and we couldn’t be prouder to support its efforts.”

Jordan said she hopes doula training serves a steppingstone for many of the people who become certified.

“We don’t want them to stop at that doula level, we want them to stay curious about health care,” she added. “So, maybe go on to become a NICU nurse or a professional midwife. Possibly an OBGYN.”

Jordan and Greene find constant gratification in their work, specifically as when it comes to the Black Womb Workers doula initiative.

“It’s just knowing we’re providing access, community and equity by putting lifesaving information back into the community,” Jordan said. “…What I love the most about my role is the opportunity to empower people to say, ‘hey take your education to help save other people’s lives through the medical field.’ People might say, ‘oh I don’t have the GPA or oh I’m too old to go back to school.’ No. This program breaks down barriers. It allows them to become that sister, that brother, that advocate for someone that’s trying to bring someone else into the world. That’s what we need more of.”

Read the article on the MI Blue Daily Website: